A Timeline of Changes: Beef Cattle Farming in North America

How Beef Cattle Farming Has Evolved Over the Years

Go Back to All BlogsPosted on: June 9, 2017

Updated on: October 21, 2025

Author: Arrowquip

SHARE:

The rapid pace of technological change has left no corner of society or industry behind, not even agriculture. It would be impossible to keep up with the food demands of our growing population if we relied on the farming methods of fifty years ago, let alone two hundred years ago. Whether improved farming techniques helped the population grow or the growing population forced innovation in agriculture, we're going to take a look at the changes in beef cattle farming in the United States and Canada.

Cattle Farming From Colonization to the Civil War

European settlers kept cattle herds in America since at least 1525. In Canada, French and British settlers introduced cattle in large numbers about a century later. For the first two centuries of colonial history, herds were smaller and mainly for community subsistence.

United States

Population growth in the United States in the early 19th century created opportunities for commercial cattle farms, which took advantage of the enormous amount of land on the Western frontier. These farmers drove their cattle back across the Appalachians or used the river and canal systems to move the herds back to the eastern population centers. This system was far from efficient, but beef was not a major part of the American diet at the time.

The population expansion in the 19th century left beef suppliers struggling to keep up with demand. Herd sizes weren't necessarily the issue. In the mid-19th century, Texas boasted ten head of cattle for every one person. But as large as the herds were in the western United States, most of the cattle were used only for their hides and tallow. It wasn't until the introduction of the refrigerated rail car in the 1860s that Western cattle farmers had a way to get their beef to the hungry East Coast markets.

Canada

Beef cattle farming in Canada would not grow beyond its subsistence and small trade roots until the settlement of the western territories. Ontario, which was not a western territory but rather close to the population center, and British Columbia dominated the Canadian cattle market after the settlement.

Lack of borders in the Midwest and Western US allowed the Canadian cattle farming industry to grow hand-in-hand with the US industry, as ranchers would drive their cattle without fear of border transgression.

Commercialization in the Late 19th Century and Beyond

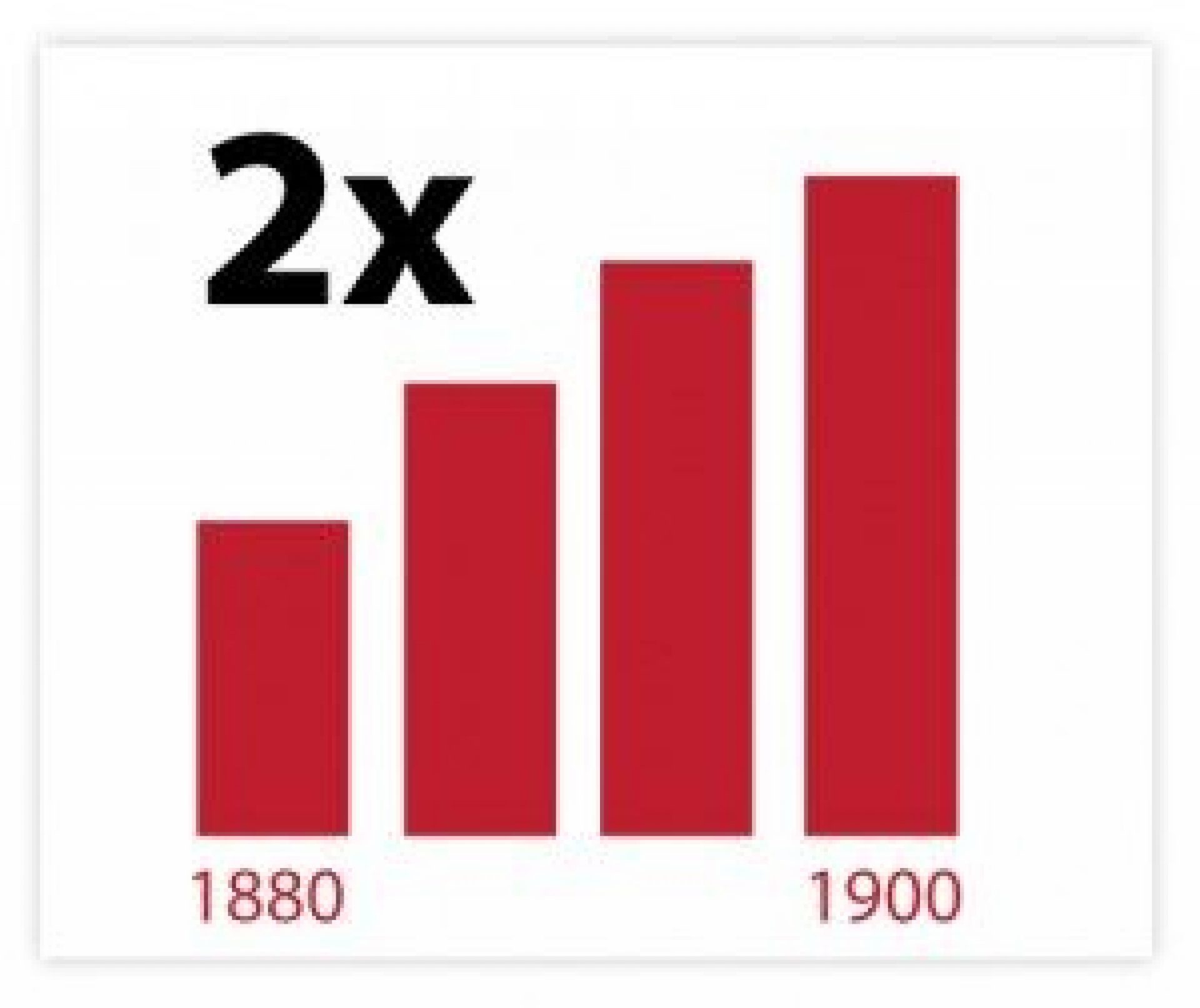

Thanks almost entirely to the refrigerated rail car, the number of cattle on Western ranches expanded rapidly. In fact, it more than doubled between 1880 and 1900.

The boom in beef production can't be explained by herd sizes alone. Prior to this huge leap in technology and its corresponding boom in the beef industry, cattle farmers had scant resources and little incentive to fatten up their cattle. They weren't selling their cattle for the meat, after all.

Now that the means existed to make the meat a profitable part of the animal, beef producers had to find a way to maximize this profit potential.

Four trends helped this along:

Cattle breed. First was the proliferation of the heartier, more muscular British breeds of cattle at the expense of the original Spanish Longhorn, introduced by Columbus and other Spanish explorers after 1493. The Longhorn wasn't replaced in the American West, but rather crossbred with the British breeds to help introduce some of their desirable traits to the Longhorn herds.

Stockyards and feedlots. The second was the rise of the Midwest stockyards and feedlots. Texas and the other Plains states had plenty of open grazing land to raise the beef. Midwestern cities such as Chicago and Kansas City, however, had access to the railroad infrastructure, and therefore they could connect the cattle farmers to the beef market. The farmers would stage cattle drives to transport the cattle to these Midwestern cities, where they would be kept in stockyards and finished in feedlots. This finishing process allowed the cattle to pack on extra muscle mass in a shorter span of time, allowing the distributors to sell more meat per head of cattle.

Processing and packaging facilities. Previously, the best way to get fresh beef to consumers in large population centers was to ship the live cattle into the city and minimize the distance between the packaging center and the end consumer. Between the 1920s and 1960s, these processing facilities moved closer to the cattle operations in the Midwest. Refrigeration technology helped to ensure the freshness of the beef as a packaged product, which is cheaper and easier to ship than live cattle.

Federal highway system. In the 1950s these highways allowed beef distributors to expand their network beyond the rail lines, which led to another explosion in growth in the beef industry.

Canada's beef processing industry grew in lock step with its American counterpart. American slaughterhouses prepared all beef for both domestic consumption and export, and the Canadians had a robust live cattle export industry as well.

Canadian cattle farmers also had to focus their energy on the more labor-intensive job of helping a herd survive their much harsher winters. Both the UK and the US provided the Canadian cattle industry with healthy markets throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.

Technological and Other Improvements

Transportation improvements alone weren't responsible for advancements in the cattle industry. Corn-based diets allowed the stockyards and feedlots to pack more muscle and fat onto the cattle.

Breeding practices have produced near-perfect cattle herds that are resistant to most natural threats such as diseases. They're also capable of producing maximum beef yields per animal without using any pharmaceuticals, chemicals and other artificial improvement practices.

The overall number of cattle has declined steadily and significantly since 1970. But thanks to improved feeding technologies and health practices, the US now produces more beef than ever before.

As with many manufacturing industries, the beef industry has benefited from economies of scale. In the last twenty years, the cattle farming sector of the industry has seen a decline of almost 175,000 operations, 144,000 of which had a cattle inventory of under 50 head.

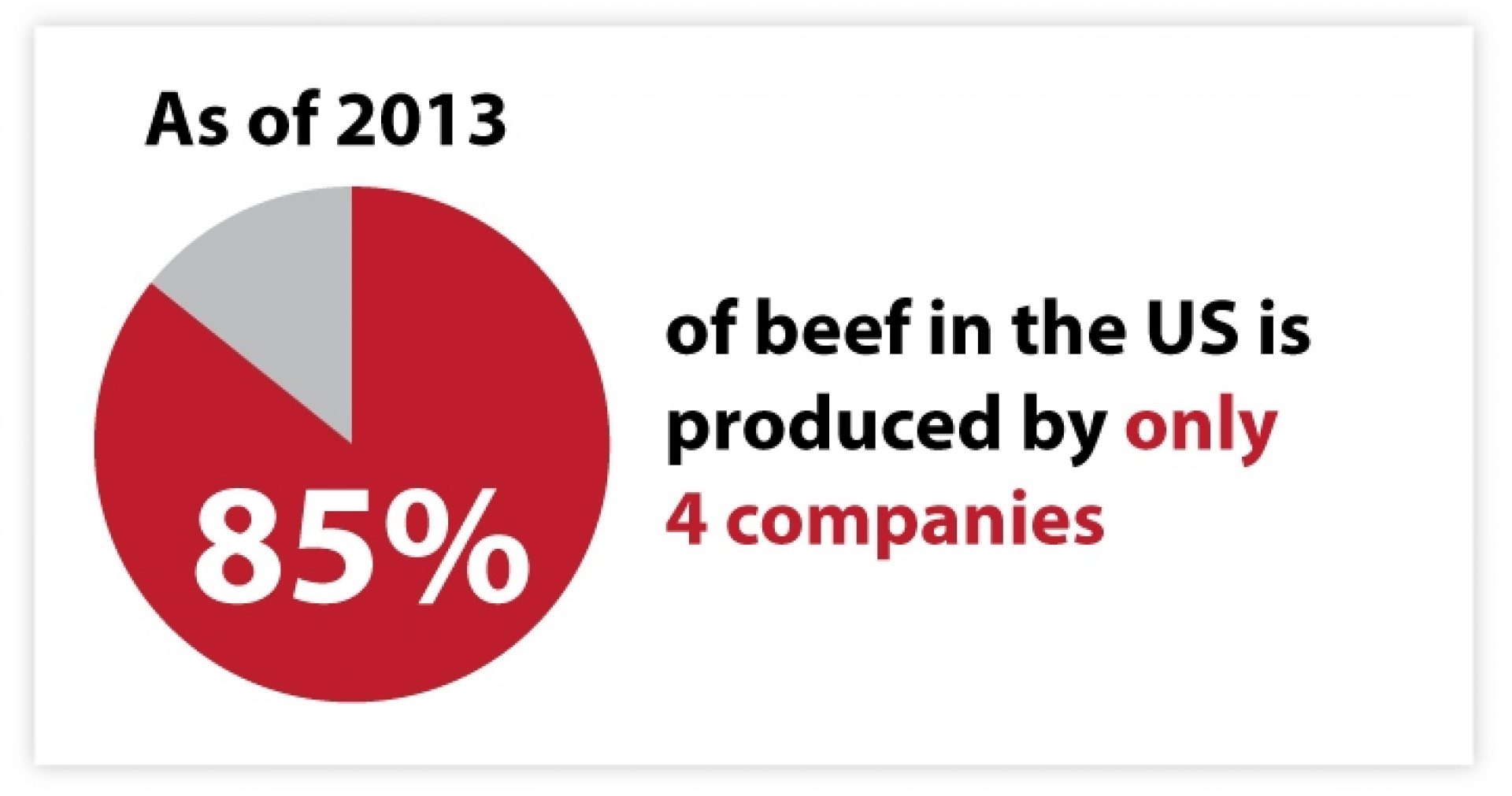

The decline of 1,000-head-capacity operations has been met with an increase in 16,000 and 32,000-head feedlots over the same time period. Processing operations have consolidated once more into a few large, efficient operations. Current machinery has allowed for the largest cattle-processing operations to process over 4,000 head of cattle a day. As of 2013, only four companies produce 85 percent of the beef in the United States: Tyson, Foods, JBS, Cargill and Smithfield Foods.

Packing plants offer a variety of products thanks to specialized machinery and streamlined operations. Rather than selling off butchered beef by the side — that is, an entire side of the cow, including all cuts of the animal — boxed beef increased the reach of the packagers by allowing customers to choose their cuts. For example, a BBQ restaurant that only offers brisket or a restaurant that only offers a filet would prefer to buy only what they need.

Trends in the Cattle Farming Industry

The general trend of the cattle industry has been one of tremendous growth over the course of the 20th and 21st centuries, as one would expect given the general trajectory of the economy as a whole.

Several reasons can be named for the steady growth of beef production:

Rise in per capita income

Growth of two-income families creating a boom in consumer income

Urbanization, meaning if you aren't going to grow your own food, you are going to buy more beef

All of these trends have continued to present day, to some degree or another. This isn't to say, however, that every figure associated with the cattle industry has grown, but declines are easily explained.

For instance, cattle inventory rose from a figure of 12.5 million heads in 1920 to a high of around 45 million in 1975.

In 2015, inventory dipped just below 30 million, the lowest figure since the 1950s. This can be explained by the growth in dressed weight of the cattle. In simplified terms, dressed weight refers to the meat and bones that make up the sellable portion of a beef carcass.

In 1975, the average dressed weight of the cattle in the US was 579 pounds. In 2015, that number was up to 817.

Overall, US beef production is indeed down from its height in the 1970s, but the value of that production has risen steadily. Most recently, the production of beef by weight declined over 10 percent between 2002 and 2014, but the value of that production more than doubled, from $27.1 billion to $60.8 billion. Beef cattle in 2015 is certainly in good shape financially.

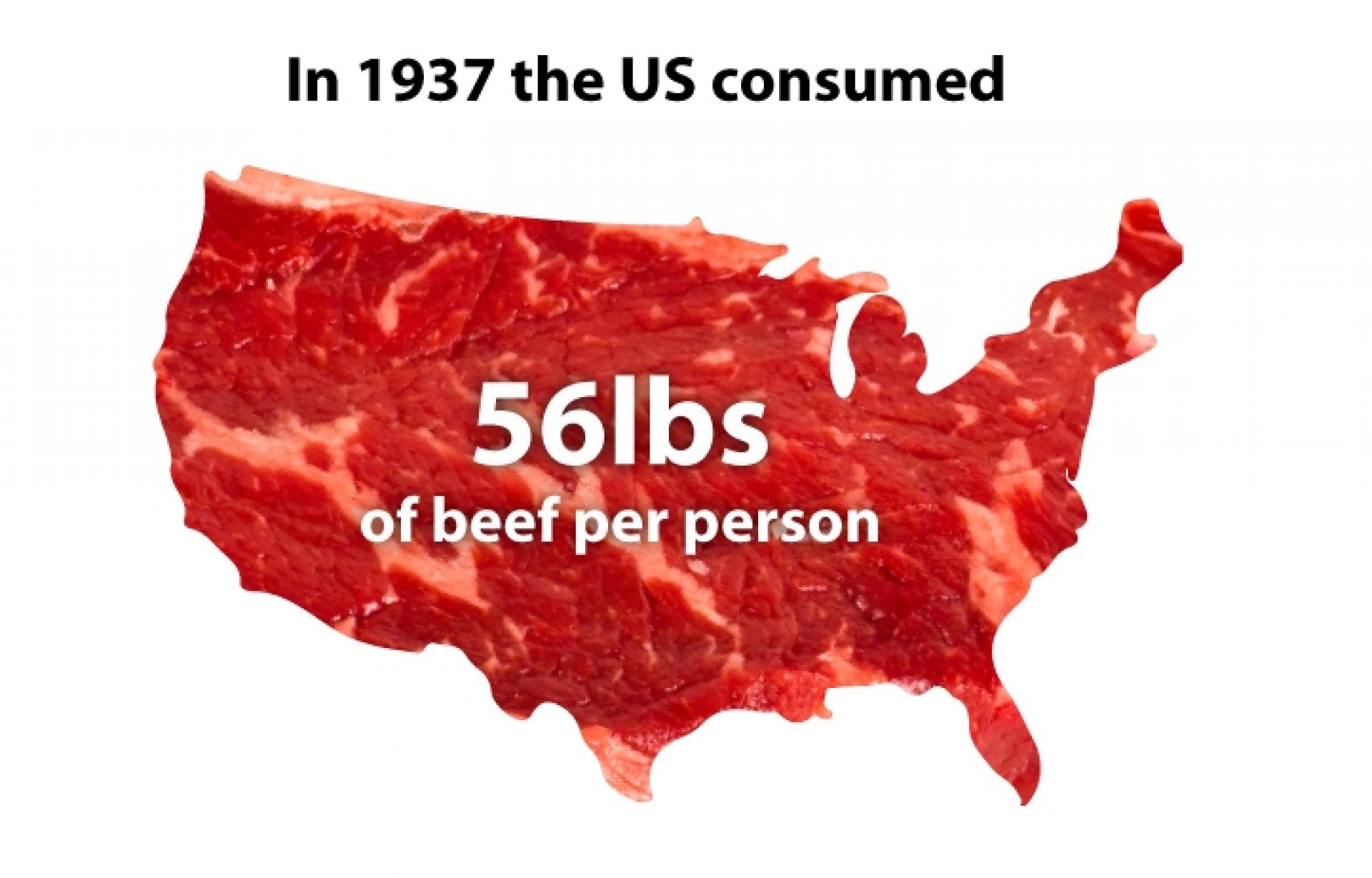

US beef consumption steadily rose until the 1970s, and has been on a precipitous decline ever since. In 1937, the US consumed 56 pounds of beef per person. By 1964, that number was up to 100 pounds per person according to some sources, while others say we reached our peak on 1976 at 94.4 pounds.

Beef Quality Grading

On the regulatory side of the industry, no program has been as visible for consumers as the USDA beef quality grading system. Despite its age, this program has also undergone changes to help keep up with the times.

In 1917, the USDA began a voluntary grading process for the beef processing industry. By 1927 the grading stamps began to appear on beef packaging.

The rules and standards have undergone several revisions over the years, but the grading system provides a standard analysis of the quality of the meat. This analysis is based on the following factors:

Physiological age of the animal at the time of slaughter

The amount of intramuscular fat, known as "marbling," present in the meat

An assessment of the yield of boneless tissue from the particular carcass

All of these factors combine to give the beef a grade using a quality grade term and a yield grade number.

The consumer-facing labels are a simplified version of the USDA grade. Beef processing facilities are not required to pay for a USDA inspector to grade their beef, but choosing not to means forfeiting the marketing clout and pricing stability that comes with the grades.

The grades are as follows:

Prime. This is the highest grade assigned by the USDA. It's reserved for beef with the most marbling and best texture. The overwhelming majority of beef that receives this grade is sold to the hotel and restaurant industry.

Choice. The second-highest USDA grade, beef earning this label sells for a higher price in the retail market. It contains a fair amount of marbling and a pleasing texture.

Select. This is the lowest of the USDA grades. It's likely found on the label at a supermarket and contains little or no marbling, and an unremarkable texture.

Standard and Commercial. Beef receiving these grades will rarely be marked with the USDA shields. It's most likely sold at supermarkets as store brand or stew meat.

Utility, Cutter and Canner. These last three grades are not sold to the consumer as is. They're instead used for anything from hot dogs to dog food.

Beef marketers used to label their products as "Grade A Prime" or "Grade A Choice." The letter grades A through E were used to assign a value to the maturity of the carcass.

Almost all cattle farmers and processors can afford to bring their beef to market at the highest quality Grade A designation. The maturity letter grades are now combined with the marbling grading to produce the final Prime/Choice/Select designation. As a result, one will no longer see a letter grade on beef packaging.

The Future of Beef Cattle Farming

Beef consumption trends will continue, and there are a few factors to consider for the future. As the American diet evolves and consumers gain a better understanding of their food, the role of different proteins will continue to evolve.

The continuing discussion of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) and other bioengineering technologies will certainly impact all aspects of the agriculture industry. Foreign markets will provide both new opportunities for growth and bring new competition to the domestic beef industry.

It is difficult to predict what the future will look like, but one prediction is easy: the industry will continue to evolve.